The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 2E – Nebraska Lore

Interviews, Life Histories and Folklore

Interviews provided some of the most interesting raw material that went into Project publications and gave the writers themes they could develop further by going to other sources. At first, Project workers interviewed rather haphazardly, seeking information only on events about which they planned to write: When was that building first erected and how many times did it burn? Umland recalled one Project field worker who could not decide how to reconcile the elevator man’s account of the history of one of Lincoln’s opera houses with information from the city directory and different accounts by unnamed “others.”

Project interviewers sought first-person accounts of Nebraska life that would reveal the struggles and ingenuity of ordinary people. These life histories, good regionalists believed, would reveal the true creative depth of American culture in its local and historical unfolding. Life histories collected in Nebraska address a fascinating array of subjects, including elections, the rise of the Populist Party, the Farmer’s Alliance protests of the 1890s, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, local folklore, outlaws, horse-trading, Civil War battles, slavery, African-American life in Omaha, Native-American culture and history, European immigrants, the Oregon Trail, pioneer customs, blizzards, prairie fires and grasshopper plagues, to name but a few. The Nebraska Project also emphasized Pioneer stories and how different ethnic traditions shaped everything from weddings and funerals, to planting, cooking, holiday celebrations, dancing and medicinal practices.

In The Dream and the Deal, Jerre Mangione traced initial instructions to collect life histories and folklore to Washington, and the interests of Henry Alsberg, Director of the Federal Writers’ Project, and of John A. Lomax and Benjamin Botkin, his successive folklore editors. Some state projects received these instructions “with derision.” Yet in Nebraska, Mangione notes, as in some southern states, Project workers and the local community took an enthusiastic interest in gathering folklore materials.

The Nebraska Project decided to devote special attention to folklore and pioneer reminiscences. It eventually published some thirty folklore pamphlets on topics that included Cowboy Songs, Pioneer Dance Calls, Santee-Sioux Legends, Nebraska Cattle Brands, and Indian Ghost Legends, among others. Two pamphlets, Farmers Alliance Songs of the 1890s and More Farmers Alliance Songs of the 1890s reflected the deep roots of populism in William Jennings Bryan’s home state and the resonance of those protests in the hard times of the 1930s.

On February 7, 1940, the Sunday edition of the New York Times included a write up of the Nebraska Project’s pamphlet Pioneer Recollections under the title “Life on the Frontier Vividly Recalled.” The story told how now aged residents of the state recalled the earliest days of white settlement, including “Indian Massacres, Grasshopper Plagues and Claim-Jumping.” The story included a poignant vision of the beauty of the unsettled prairies. “The wild roses, in the ’70’s, were very thick with red blooms that could be seen for miles away,” recalled a Lincoln woman who came to the state in a covered wagon in 1872. “They had red berries on them larger than your thumb. Buffaloes could be seen wallowing in the mud along small streams.” It was beautiful, but disconcerting too, “I can remember looking at the rolling grass… and how it used to make me seasick because it looked exactly like water; sometimes I could see mirages in it.” The Times‘s story ended with the observation that the pamphlets had “attracted wide attention among students of American culture.”

As Nebraska’s Project workers gathered stories from old timers for the Nebraska Guide and local guides, and interviewed them about daily life, folk culture and local history, they put together a unique collection of narratives and anecdotes that became Nebraska’s contribution to the American Life Histories. In the minds of the Federal administrators, these life histories, recording the struggles, passions, and creativity of ordinary people, would be the foundation of a new understanding of “composite America,” a civilization enriched by the dreams and dynamism of ethnic, national, and racial minorities. This vision grew from a new appreciation of the complex brew of ethnic and national cultures that first began to take shape in Willa Cather’s immigrant novels. The appeal of this understanding of American life grew enormously as Americans watched the vicious nationalisms of fascism and Nazism take hold of old Europe.

The Library of Congress now makes its American Life Histories collection available on-line. The reader who surveys Nebraska’s contribution to the on-line collection at random will find enormous variation in the quality and interest of the interviews. This variation reflects the varying purposes of the interviews, different levels of interviewer skill, and the differing storytelling abilities of informants. The best of these accounts preserve a rich record of history and individual experience that would have been utterly lost without the Federal Writers’ Project. These include pioneer stories, humor, songs about Nebraska, and the like, but extend to other matters as well. Fred Dixon’s careful interviews of African-Americans preserved memories of slavery, and of early African-American history in Omaha and the rest of the state that would otherwise have been lost with a passing generation. Dad Streeter’s wonderful stories, including a story about his father, “A Preacher Tries Farming” in the American Life Histories (not a direct link), and his contributions to the folklore pamphlets, would never have seen the light of day without the Writers’ Project.

A Community of Writers

There were no well known or experienced writers among the employees of the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project. Neither Jake Gable’s boy’s adventure book, nor his bibliography of Robin Hood stories, published while he was Project director, put him in the same league with the rising stars or established writers sometimes employed by other state Projects. Only two Project writers, Loren Eiseley and Weldon Kees, would, someday, gain real fame as writers. Rudolph Umland became Prairie Schooner‘s most prolific contributor, and, as a hobby, wrote book reviews for the Kansas City Star and the odd magazine article, but he pursued a post World War II career as a Federal bureaucrat.

It required a kind of magic to create a functioning organization out of the assortment of inexperienced and previously unemployed people who, it was believed, might become writers, if assigned the task. Umland, with help from his friends Lowry Wimberly and Mari Sandoz, helped create an informal community among Project workers that sustained a vigorous and long-lived discussion of Nebraska lore. In this informal setting Wimberly and Sandoz urged the Project toward success, offering invaluable knowledge, advice, and stories about their own experiences. When the work began to bear fruit, they read and offered editorial advice on some of the Project’s manuscripts.

Nebraska Writers’ Project Christmas party at Jake Gable’s house, December, 1936.

Wimberly had sent many of his Prairie Schooner contributors and students to the Project. He “followed the ups-and-downs of the project, the ridicule and sometimes acclaim it earned in the press, with an avid interest.” Sitting with Umland in Grasmick’s bar sometime in 1936 Wimberly expressed the hope that the Writers’ Project would make publishers recognize what an interesting place Nebraska could be. “There’s plenty of source material here… right here in this tavern in Lincoln, Nebraska, to write a dozen novels. Think of the lives some of these beerdrinkers have lived. There is all the humor, the tragedy, the foolishness that’s needed.” Wimberly was, just as Umland described him, a fierce spiritual aristocrat “who could be as common as an old shoe.”

The acclaim and admiration that Wimberly’s beloved Prairie Schooner had won from critics and friends of literature around the nation earned him scant credit with the University administration. He had to beg for a small subvention for each issue from an increasingly unsympathetic chancellor. In the summer, 1937 issue of the Schooner, Wimberly hinted that readers might be looking at the last issue of the magazine. He was thinking he should stop accepting new manuscripts.

In those years, Lincoln’s literary community revolved around the Prairie Schooner. Mari Sandoz, Umland noticed, read each issue from cover to cover just as soon as it came into her hands. The Project’s writers gathered regularly in Sandoz’s apartment, or elsewhere for “talk-fests.” These were lighthearted and informal affairs, where once, in her apartment, Mari Sandoz demonstrated her knowledge of Polish dances, a skill she picked up either as a young girl or as a country schoolteacher. Sandoz’s years of misery were behind her, and she seems to have been at the center of many of the writers’ gatherings. Umland recalled that she “could chatter endlessly, hoot and laugh lightheartedly in those years in Lincoln.” Conversation at these gatherings often dissected writing that had appeared in the Schooner, or probed the latest news or rumors about Wimberly and his epic campaign to keep the little magazine alive.

News of the impending demise of the Schooner led the writers to the realization that they could write about matters other than history, Umland recalled. Letters of protest and petitions deluged the chancellor and regents. Who knew, Umland asked, “that half the signatures… were those of WPA workers who had never seen a copy of the magazine.” Mari Sandoz wrote wrote to the chancellor as well. Wimberly first heard of the flood of letters when called to the chancellor’s office. He was told that the Schooner would be funded for the year, and that there were to be no more rumors that the magazine was about to expire.

With this brusque gesture, the Schooner finally gained acceptance as a worthwhile–or at least inevitable–University emblem and institution. The magazine was never again in quite so much peril. “The sudden shower of letters always remained a puzzle to Wimberly,” Umland says. But those letters, Wimberly told his readers in the next issue of the Schooner, had saved the day.

Wimberly and Sandoz continued to keep abreast of all the news about the Project. Until he left the project for the military in 1941, Umland, sometimes joined by other writers, sat down with Wimberly almost every week at Grasmicks, the Bull Head, or some other tavern for a rambling conversation over a beer or two (two was always the limit, Umland remembered). Just as often, Umland met Mari Sandoz in the coffee shop at the bus depot.

In May of 1958, Mari Sandoz returned to Lincoln for a visit, and Umland accompanied her on a bus trip to a speaking engagement in Omaha. Along the way, Umland said, Mari talked non-stop; she recalled people who had worked on the Writers Project, and said that in those years (this is Umland’s paraphrase) “nobody had much money… but it hadn’t seemed to matter; they weren’t unhappy years.” Sandoz had “lived on day old cinammon rolls from Acme bakery and day-old chicken pies from Miller and Paine’s and had survived.” Once again, and for the last time, they chatted about Wimberly. Wimberly, she said, had revived a literary consciousness that had been dormant in Lincoln since the 1890s. He created an atmosphere that got people to think about writing and to try to write themselves. Without this atmosphere and his encouragement she said, she would never have been able to keep on writing and rewriting her manuscript of Old Jules. She intended to write an autobiography and wanted especially to get the story of those years on paper. Her other projects kept her much too busy though, and she never did write about those times.

Writers and Depression

Mari Sandoz could look back on the late 1920s and 1930s as a kind of golden age for Lincoln writers. Mari’s early life gave her a tough-mindedness and a hard grip on life’s essentials–her life’s essentials. Her own work and the community of writers meant more to her than a full stomach. Her committments shielded her from the full uncertainty and misery of the Depression.

For many of its employees, the Writers’ Project too, provided not just work, but the shelter of social connection and a sense of purpose. This was true all across the country. “We were all like people on a raft, sharing a world of common disaster,” federal administrator Lawrence Morris recalled in an interview with Jerre Mangione. A Nebraska employee recalled that just before the Project offered her work, she and her husband, both unable to find employment and without food in their apartment, had very seriously discussed suicide. Workers’ memories of isolation and their fears of losing this shelter account for some of the intensity of the friendships and lively social life that emerged within the Nebraska Project.

The Nebraska Project documented the onset and effects of the Depression in the state. Among the life histories collected by the Project is a banker’s account of the bank failures that began in the early 1920s as agricultural prices and the value of land fell after World War I. This is a window on how early hard times began in Nebraska. Times were hard in the state long before the 1930s, when the rest of the country found itself in trouble, and the ‘official’ Depression began.

Every time a Project worker interviewed an informant to gather folklore or local history, the worker filled out a form that described the circumstances of the interview. Most of these interviews seem to have taken place at the informant’s residence, and in these cases the worker described the room and set down their impression of the informant’s current circumstances. Some of these descriptions testified to the most desperate poverty.

The desperate circumstances of individuals also intruded into the administration of the Nebraska Project in a variety of ways. Umland and his director, Jake Gable, tried hard to avoid releasing people who otherwise had no means of support, even if these people were not well suited to the work at hand. Periodic crises forced them to let go of even the most desperate. In 1939 such a crisis forced the Project to let go of J.H. Norris, an older man known to Umland as a creative storyteller and folklore collector. Norris’s letters to Umland described his frantic effort to get re-certified as eligible for the relief rolls, a necessary prerequisite for reapplying for his old job or any other WPA work. Later he pleaded for re-assignment to the Writers’ Project. “I’m literally on the rocks, but I’ll be damned if I ever go without eating for three days as I did a few years ago right here in this room,” Norris wrote.

These and similar events notwithstanding, the Depression entered into its second half during the first year of the Project. Work programs like the WPA and the Project itself, as well as more jobs and better prices in the private sector, were making life easier. The consumer economy was reviving. The American Guide Series itself testified to this. The automobile tours outlined in every State guidebook reflected the new role of the automobile in American life. More and more people owned an automobile and more and more had time to take a few days off and see some of the country.

Characters

As a relief program, the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project needed to accept and make the most of employees whose qualifications for the job at hand were less than obvious. There were many hardworking and competent workers, and a very few geniuses (we discuss the geniuses later). There were others whose temperament or background did not fit the work, or who departed on some eccentric trajectory of their own that left the project behind.

The tour editor for the Nebraska Guide, Umland recalled, wrote a piece that clearly needed revision. Upon hearing that it had been sent to a rewrite editor, the tour editor responded with bitter recriminations. She was a well known Nebraska poetess, and she did not think her work required revision. “I have 20 years of editorial experience and am the author of several books,” she told Umland. The editor, she was certain would destroy her essay, “He’ll take away all its color, destroy its beauty!” Umland felt that the editing improved the piece by getting rid of purple prose and excess verbiage. The poetess took this as an intolerable insult, and left the project.

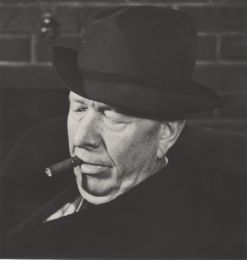

Local Democratic party politics saddled the Writers’ Project with Henry Richmond, a former newspaper reporter and politician, who had acquired the epithet of “Colonel,” as politicians of the time sometimes did, without a scrap of military experience. Colonel Richmond had been a reporter in Red Cloud when Willa Cather was a girl, a red hot populist editorialist and newspaper editor, a reporter again, a close associate of William Jennings Bryan, President of the Nebraska Press Association, a state representative, and in later years a city health inspector in Omaha. He was a wonderful storyteller and informant about Nebraska politics, and Umland enjoyed his company. But Colonel Richmond was so deeply mired in his political world that he would always be too busy reminiscing and scheming to contribute anything at all to the Writers’ Project.

Henry Richmond, circa 1937

Umland wrote a wonderful short biography of Richmond for the Fall, 1941 issue of the Prairie Schooner. Richmond was so much the politician, he recounted, that on a trip to Washington, D.C. he was mistaken for a former Congressman. He was recognized as such by serving members of the House, who could not remember his name, but were certain that they knew him. He made it onto the House floor by claiming to be a former member, and dined in the Senate restaurant with another politician who recalled meeting him in Austin, Texas, a town he had never visited. “You do not mistake him for a banker, a professor, or a drug clerk as you do many politicians of the new school,” Umland wrote. “You immediately know he is a politician; you sense that he has a finger in the political pie….”

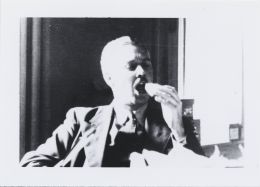

At Umland’s suggestion and on the basis of a formal letter of recommendation by Lowry Wimberly, Jacob Harris (“Jake”) Gable was appointed Director of the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project in July of 1936. Gable, an unemployed librarian, had been one of the student founding editors of Prairie Schooner in 1927. Gable’s legendary self-adulation was a constant topic of conversation and source of amusement for Umland and Wimberly. “He frequently interrupted his work to pound on his desk with his fists and proclaim himself the greatest writer, the greatest editor, the greatest bibliographer, the greatest gourmet who ever lived.” He was loud, boisterous and cheerful. Wimberly thought him too gregarious to ever be much of a writer. He could not bear to be alone, and built a mutual admiration society among some of the employees at the Project. He convinced himself that he was a great man. “Jake comes at you with head up and cheeks puffed out like those of a squirrel,” Wimberly once said.

Gable reorganized the Project and was a brilliant promoter who left the research and editing to Umland. His abilities so impressed the Washington administrators that he was appointed regional field administrator, a position he loved because he got to attend Washington parties and travel as a bigwig. As time went on, however, Gable grew careless, he spent over his budget and he used his time at the office to work on his own book on photography. By 1939, Gable, a married man with children, had become enamoured of one of his younger female employees. He sat, Umland recalled, drumming on his desktop with his fingers, humming “I am in love, love, love.” The scandal finally embarrassed state officials, who fired Gable. Umland would succeed him as State Director.

Jake Gable at his desk, circa 1937

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500